AI Art Generators Hide a Powerful Principle for Writers

What can you learn from the principle that allows soul-less machines to create art?

Author’s Note: One last piece from the Medium archives to tide readers over as I work on the next main entry for this newsletter. This was written in 2022, shortly after AI had been introduced. It shows its age; I felt a certain ebullience about AI back then, before the many ethical implications an critiques settled in, and you may see that in my writing. I favor AI, still, but that favorability is tempered by a long consideration of its limitations and implications. But this article, again, is about mechanics. There were specific principles at play in AI art that I considered very powerful for anybody seeking to make things—and they apply whether you’re a writer, an artist, a musician, a sculptor, or a creator of any stripe. This is the clearest statement of those principles that I have managed so far.

A Beautiful Woman Holding a Rose

The above image was generated from the phrase “a beautiful woman holding a rose.” I started with the Midjourney AI text-to-art bot. For the final pass, I upgraded Midjourney’s image using Stable Diffusion. The result is far beyond anything I can do myself.

But as I am discovering, that limitation no longer applies.

To be honest I am not sure what to say. It is hard for me to believe that we live in a world where this is now possible.

The thing that finally convinced me was repetition. Produce one image like the above and you can dismiss it. Fifty, though? Eight Bierstadt paintings of Half-Dome at Yosemite, shrouded in morning mist? A dozen sunsets in the vivid style of Leonid Afremov? Daguerreotype portraits of grizzly bears wearing sombreros?

At some point, I became a believer. Computers can now create art.

How the hell did this happen?

As it turns out, the question “how the hell did this happen?” is a useful one. Smart people have been asking a related question (how can we make this happen?) for decades.

Now that they have their answer, asking it again for ourselves can teach us something. I am especially partial to what it can teach writers; there are lessons there for word-jockeys who want to better understand their craft.

Before the code came together, after all, someone had to reverse-engineer art itself, to answer a megaton question: how can we design a creative process so powerful that a non-sentient machine can use it to bootstrap its way to being an artist?

Call me crazy, but I think we writers can learn something from the answer to that question. Happily, the process is on clear display if you use Midjourney. I want to walk you through the creation of the image from my initial prompt (a beautiful woman holding a rose). Here it is, roughly divided into steps.

Static (0 % complete)

Midjourney starts with a panel of randomly generated static called a seed. Actually it starts with four of them; prompts are processed four times simultaneously so that the user can choose the result they like best. Below, you can see four such seeds; they are too blurry to make sense of right now. This is the raw material used to generate an image.

Basic Form (about 10% complete)

Now that you’ve seen the static, we can discuss the basic process that an AI like Midjourney uses to move from a seed to a completed work.

To grossly oversimplify, Midjourney starts by treating the random static as the blurred result of a “true” picture hidden underneath the noise of the random static. It then calculates how to de-noise the image.

The problem is that de-noising everything at once is way too difficult. So Midjourney splits the process into hundreds of gentle iterations. With each new iteration, the image is “nudged” to be more in line with the prompt. In the image below, you can compare the panels with the original static and see that the vague blurs and shapes have been subtly altered to become identifiable as a woman and a rose.

Structure (about 25% complete)

At some point, the image coalesces and Midjourney starts to identify the placement of smaller features within the original, broader forms.

At this point the process seems to be a negotiation; not all of the (still blurry) basic shapes lend themselves correctly to fulfilling the prompt. As a result I have seen Midjourney change blurs that look like they should be one thing (like a person) into another entirely (like a rock), in order to better fulfill its prompt.

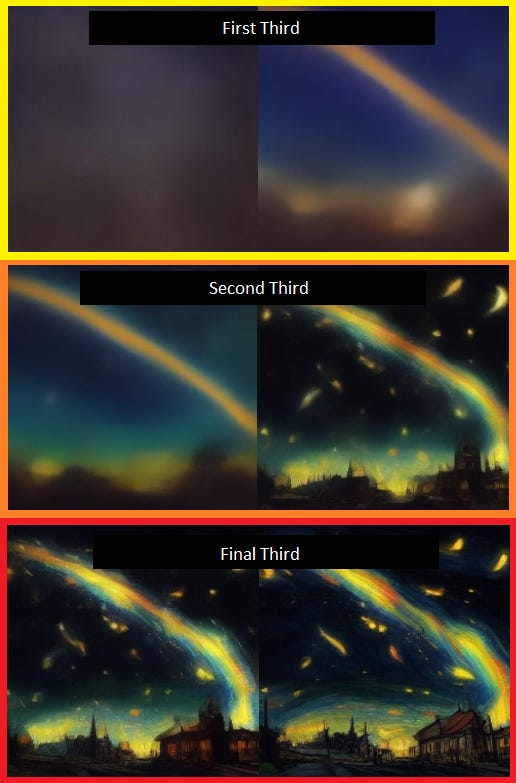

Composition (about 62% complete)

At this point in the process Midjourney has produced clearly identifiable pictures. The art could be considered complete at this point, at least in the sense that the basic composition is there, but Midjourney is only two thirds of the way complete. What’s happening?

Well, it turns out that the last third is very important. This is the point where MidJourney’s work starts to alter the details of the picture more than its form or composition.

Details (100% complete)

I am repeatedly surprised at how much an image transforms in the last third of its journey to completion. The details make the difference between a painting of a starry sky and Van Gogh’s Starry Night. An artist’s style dwells in the details, and the details also appear (in AI art) to be the place where the most errors occur. You can see the results of the final touches in the picture below.

Midjourney’s Lessons for Writers

The above portrait is the best of the bunch. It’s wonderful, of course, but can we really learn something from it? Your creative process is likely different from Midjourney’s, after all.

The brilliance of AI art, however, isn’t that it gives you a perfect process to replace your own. Rather, it offers you a new way of thinking about your work that can be flexibly adapted to your own writing style. You can use its principles to enhance your writing, diagnose problems, and break through mental blocks. Here are a few principles for you to consider.

Principle one: Iterate, iterate, iterate

The one principle I hope you take from this article is that iteration is powerful. In fact, many common pieces of advice about writing are actually suggestions to iterate.

For example, here’s an old debate; should you outline, or should you just free-write a shitty first draft and then polish it to create a better one? These seem like opposites, but both are actually just forms of iteration. Pick the one that makes you feel confident, and go.

The principle behind iteration is that multiple passes reduce the complexity of creation by spreading it across episodes. Producing great work in one pass requires intense mental effort — and this is true for both you and a computer. Producing great work over multiple passes reduces the “computation” load drastically so that no single iteration is too complex for your hardware to accomplish.

You can apply this immediately to your workflow if you procrastinate. Procrastination is a way of avoiding the pain of a high computational burden until you have a burst of last-minute adrenaline to help you handle it. People describe this as a feeling that a mental “switch” has been flipped.

Want to work without waiting for the switch to flip? Iterate. Reduce the burden so that you don’t need adrenaline. Iteration is the flowing river that carves away the mountainous impossible. Start gently, take several passes to clarify your ideas, and several more to write your draft. Each pass becomes the raw material that feeds into the next round of iteration.

Principle two: Seed and prompt

In the world of AI-generated art, creation results from the collision of a seed and a prompt.

The prompt is a user’s instructions to the AI. But writers have their own prompts — the high-level goals they set for a creative project (e.g. write an essay on surveillance capitalism).

The seed is a panel of randomly generated static. Life doesn’t offer writers many panels of actual random static, but we do still have our own form of randomness to use as seed material; the quirky details of our own lived experience.

You can combine a prompt (your big goal) with any number of seeds, each resulting in a unique creation. Your essay on surveillance capitalism will look radically different if you start by considering your iPad rather than the light bulb in your room. They may have the same core intent, but the seed(s) you choose will alter how it is expressed.

Midjourney starts with four seeds. Why? Well, variety allows the user to examine the result of the same prompt across multiple seeds, to pick what works best. It’s a great trick, and you can do it, too.

Changing seeds is powerful because it breaks an artist’s fixation on a single way of achieving their goals. Are you struggling with a project? Try changing seeds; keep your big vision, but express it through a different set of random material drawn from your life. This creative recycling is a great way to break free of a mental rut.

Principle three: The final third happens after composition is done

When I was younger I stocked shelves at a major retail store. Each night our final task was to “face” the aisles, which meant arranging every item in a perfect row, each sticking off of the shelf by a quarter inch.

That must sound ridiculous. But having done it, I can share an insight; there is something psychologically different about an aisle where everything is perfectly aligned. It is the visual equivalent of a firecracker. And it hinges on getting the details just right.

During AI art generation, when you request that a prompt be executed in the style of a specific artist (for example, the inimitable Van Gogh), some of the artist’s preferences regarding form and color appear during the first two thirds of the rendering, but it is only after the 60% mark that the subtleties that identify an artist’s style will appear.

In fact, for many artists who use more conventional form and color, the signature characteristics that mimic their style don’t appear at all until the final third. The details make almost all of the difference.

Our mind has emotional mechanisms triggered by details so subtle that we overlook them until they line up together in a way that leaves us stupefied. Their effects are profound; they are the difference between a face that you hardly notice and one that leaves you breathless. And they all happen below that quarter-inch level. That is where quality dwells — and also the markers of an artist’s unique style.

In Midjourney those details aren’t even touched until the last third of the composition process — after the composition already looks complete. Why? Well, in AI, it’s because the main picture needs to be resolved before the detail work can commence.

But this principle applies to your prose as well. Are you the kind of writer who completes the final third? That’s the work you do after your piece already looks complete to you. That’s your chance to polish the details, and shine.

I thought I was going to dislike this article because I’m not a fan of AI images, but reading this reminded me that I can learn from something I dislike! In fact, it’s good practice to do that sometimes.

Another fascinating piece. I love your idea of the seed. When we write in our Prompt of the Week Zoom, we use an image prompt and then everyone generates a list of words, and we make a community list by taking one from each person. Those may be our seeds: often I will take off from just one and leave the rest behind, and I know that if I took off from a different word, something entirely different would emerge. Which, I have to say, is very confidence-building! If you can write 2, you can write 20. This four-part Midjourney is also very inspiring because it demonstrates that 75% of what you make is what gets you the part you want. Robert McKee said that 90% of what you write is research - what you have to write to get to the 10% you'll use.